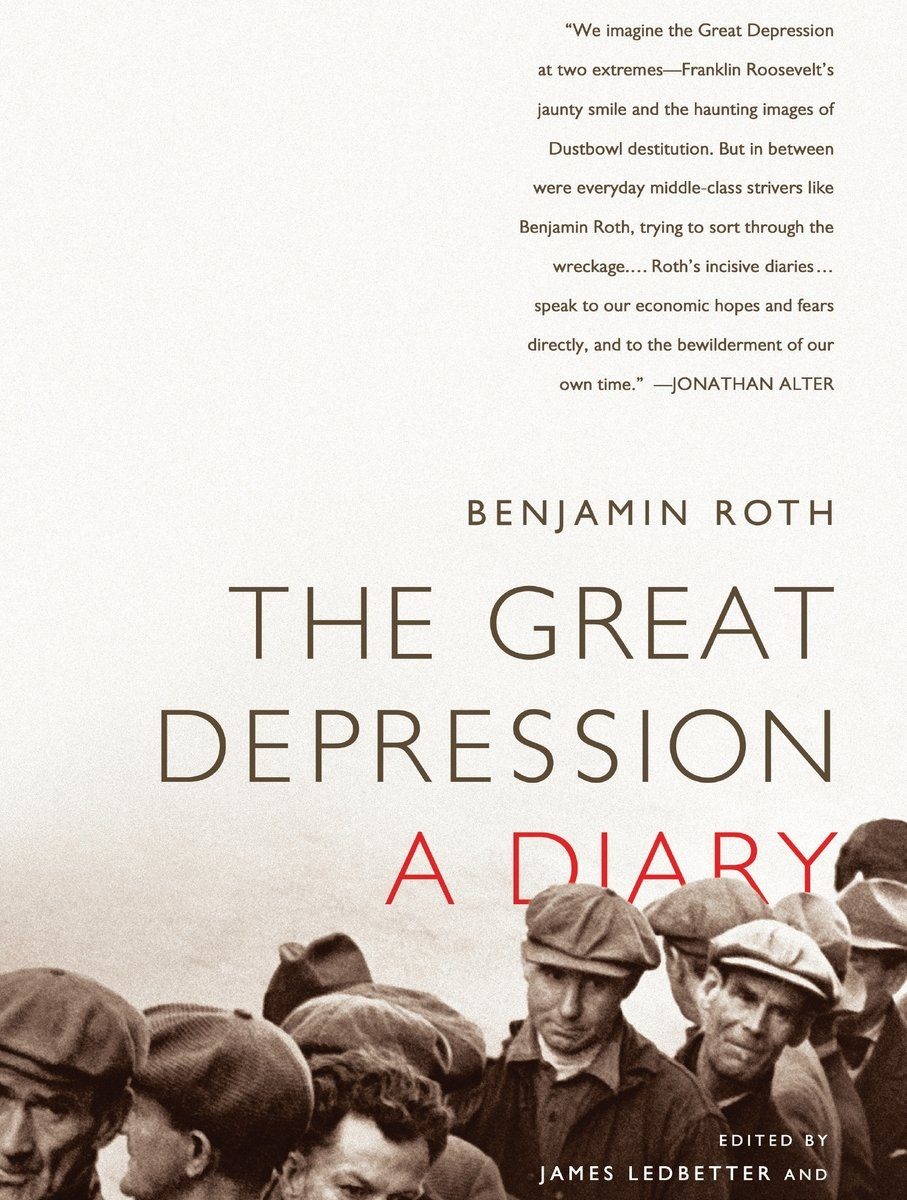

The Great Depression, A Diary (or why buying low is so hard)

Benjamin Roth was a young lawyer living and working in Youngstown, Ohio during the Great Depression. In June of 1931, just over 19 months after the calamitous stock market crash in late October of 1929, Roth started journaling his thoughts about the stock market, banks, his law practice, politics, and investment opportunities. After the stock market crashed in 2008, Roth’s son, Daniel, knew it was time to honor his father’s memory by publishing his father’s writings. The timing was right, and although we are now 8 years removed from the stock market lows of 2009, Roth’s accounts of the Great Depression refreshed my thoughts of our most recent economic catastrophe.

The importance of this book

Beware the danger of hindsight bias. Here’s the definition: “the inclination, after an event has occurred, to see the event as having been predictable, despite there having been little or no objective basis for predicting it” It is a near impossibility to keep our hindsight bias from kicking into gear when examining historical events. Our bias often leads us to overconfidence, luring us into making decisions for the wrong reasons, possibly damaging our lives and our loved ones along the way. That is exactly why Roth’s personal account of the events and people of the 1930s is so valuable. When considering the Great Depression, I have been quick to make judgement on how leaders, business people, and families should have reacted if they would have only kept their calm and made rational decisions. I can’t say how representative Roth’s reactions to the Depression were of all who lived through it, but he is proof that there were people able to keep their emotions in check while the economy was collapsing around them. Roth’s dispassion is remarkable, especially considering he was responsible for providing for his wife and 3 young children during that time. But Roth was not without reasons for hope even during dire economic times. He was an educated professional, and as an educated man, he had knowledge of history to rely upon. Most historical market charts used today start in the 1920s which causes the history of markets before the 20s to be downplayed, if not forgotten. However, Roth had a high awareness, not only of the stock market and investments in the 1920s, but also of economic recessions in the United States prior to the Great Depression. Roth didn’t even own stock when the Great Crash hit (only 2.5% of Americans did), but he was highly aware of stock markets happenings and history. Roth often references the crashes and recessions of the 19th century, and uses them to forecast the length, severity, and opportunity of the Great Depression. Many of his predictions are far off (just like everyone else’s of that time…and today). But many of his insights were remarkable. The richest part of Roth’s diary is his predictions of the future and the later comments he made about his predictions and whether they were right or wrong or very wrong. But therein lies the tragedy of Roth’s diary: he had fantastic insights and admirable emotional self control, yet he was still unable to take advantage of the investment opportunities the Depression offered. In fact, only an elite class was able to take advantage of the rock bottom asset prices because only they had surplus income/capital after they made sure they could provide for their families.

Why buying low is so hard

Starvation is not a threat in 21st century United States, and it likely wouldn’t be even if another depression hit. But the same dilemma that kept Roth from taking advantage of panic prices in assets in the 30s still keep people from doing the same today. Why is that? The dilemma is that the only time assets lose significant value is when the economic stability of the future is jeopardized and uncertain. It’s at that moment when a working family can’t rely on their ability to earn an income, because their business may dry up or they may be laid off. So instead of looking for investment deals, a family pays off debt to lower their risk, or they increase their savings, or they use all they have to buy necessities. And the opportunity of a lifetime drifts by. However, hindsight bias kicks in again. If we truly knew the opportunity of 1932 or 1939 or even 2009, there is no doubt we would have made some radical choices to get any assets we could invested in the stock market or other assets like real estate. But in the midst of those times, investing looks like foolishness, not opportunism. Most discouraging about those missed opportunities is that even when someone recognizes the opportunity and has the resources to take advantage of the opportunity, it’s still not certain they’ll profit! Roth tells the story of a friend who had the wherewithal to buy 1000 shares of Warner stock in 1935 for 3 ⅛. The stock went to 18 in two years turning a approximately $3,000 investment into $18,000. Instead of selling out, his friend borrowed money on margin to buy more stocks. The crash of 1937 came shortly after, and his friend lost everything. Even someone who maintained the optimism to invest got taken down by the market…if only he had not borrowed to invest.

Lessons for today

Roth comments often on the dangers of borrowing money to invest in anything. Sure, in a rising market it makes an investor much more profitable to borrow to invest. But markets have never, ever sustained their rises indefinitely, and at times, you get entire decades when the market crashes frequently, decimating anyone who has borrowed to invest. Roth claims that every single person he knew who had borrowed to invest was wiped out in the 1930s. Roth became a student of investing during the Depression, and he shares a lot of his education in his diary. Most of this investment advice is very conservative in nature, but an ultra conservative investment strategy is the only way investors didn’t lose their shirt in the 1930s. Today, many people are comfortable taking considerably more risk than Roth would recommend in the late 30s. And if we never hit another depression like the Great one, then it is a wise strategy. But is it a guarantee that we won’t hit another depression as long and deep as the Great Depression? Absolutely not. However, is it even remotely likely? That’s where the real debate lies. Much has changed since the 1930s. Our financial system today is much different from the system of Roth’s time. Perhaps we have the mechanisms to avoid another depression…or perhaps it’s arrogant to think we are different from those in the generations before us. And that to me is the greatest value of this book. Although we live in very different times, we are not so different than the generations before us. We can learn from what they went through, but we cannot claim we have a superior enlightenment that will protect us from all catastrophe. We have to live and make decisions in humility, recognizing our own naivety and limitations. If we do so, we still may fall victim to the disruptive forces of this world, but we will have the strongest defense available to us: the willingness to educate ourselves.

Recommendation

I can’t recommend this book to every reader. Roth’s inclination to make investment strategy a major theme of his writings will bore and disengage many. To those who enjoy investment insights and the stock market, Roth’s book, along with editor’s James Ledbetter’s insight, are guaranteed to entertain and educate. If you don’t fancy stock talk, I don’t recommend this book. However, it is essential that everyone spend time educating themselves about the Great Depression to 1) learn to be thankful for the era of plenty in which we currently live, 2) to humbly recognize how vulnerable the complex systems around us are, and 3) to have a basis for how to react in the case we go through something similar…or worse. No matter what lies ahead of us, ultimately, if we understand the true nature of this world…the best is yet to come.